I was given a gift. And it is something that I longed for. In September 2021, I was offered an artist’s residency at Hawkwood – Centre for Future Thinking – here in the Cotswolds. It was supposed to be a time of research and dedicating this time to work on my creative practice and possibly starting deepening a project that I had previously outlined in my honest entreaty when applying for the opportunity thanks also to the generosity of The Francis W Reckitt Arts Trust.

I had previously visited Hawkwood several times on various occasions (films, presentations, festivals, talks) since I moved to the area but never occurred to me back then to be one day one of their artists in residency. Fortunate. Just a few weeks before and after we returned from a too-hot Milan trip, I was telling my husband how much I needed a ‘holiday’ from everything and needed space to focus on my ceramic work.

Be Careful What You Wish For!!

A few weeks later I arrived, fully landed body and mind, after weeks of preparation. The weather was clear and wet just the first sign and colour of autumn – beautiful. I had with me my bags of clay and sculpting tools. My workspace was the Woodland Sanctuary, nestled among the trees.

A bare, simple but warm and welcoming large tree-house perfectly integrated in the woods and originally created to support quiet contemplation and silence for the community. The Woodland Sanctuary was indeed a Sanctuary. I found myself lost and found, and probably this is what a sanctuary does. I struggled the first few days while embracing the silence and the nature around the space and the more I let go of the pressure from life and welcoming myself, and the more I wanted to stay at the Sanctuary. I only decided to finish the work-day by the time dinner was served mostly because I didn’t want to walk back and forth after dinner in the dark (or with a torch). And this also offered me a work routine that fitted perfectly with the structure of the residency and the communal meals, an ideal place for interaction and comparing notes with other residencies. Without mentioning delicious food served every day – several times a day – mostly directly from their well-cared walled garden. It was such a luxury both for the quality of the food and for being nourished and the attention to detail. Spoiled. And to add to this, there is the bonus of the wonderful view across the valley and beyond.

A week sounds at first a short time but it’s at the same time a long time – to be on your own (mostly) and with your thoughts. The residency was a rare opportunity for me for contemplation and reflection and offered the stimulus for a maker to create a small body of work.

During my ‘going away’ I wanted to be able to ‘retreat ‘ with myself in a dedicated place while opening up my energy and creativity deeply into my artistic discipline. I wanted to try exploring my silence and be in a non-domestic, familiar, or professional setting to create what I am working on with creating and exploring. The setting was perfect for what I needed and perfect timing. The sanctuary, the gardens, the view, the setting …

I also roamed the main house taking pictures and spending extended periods just sitting, looking and thinking. Thinking. Hawkwood is a place rich in visual nourishment. My favourite spot (and I am sure I am not the only one) is one of the window seats in the large rooms on the ground floors – but they were mostly occupied by other activities, so I used popping by only when I could or other groups had left.

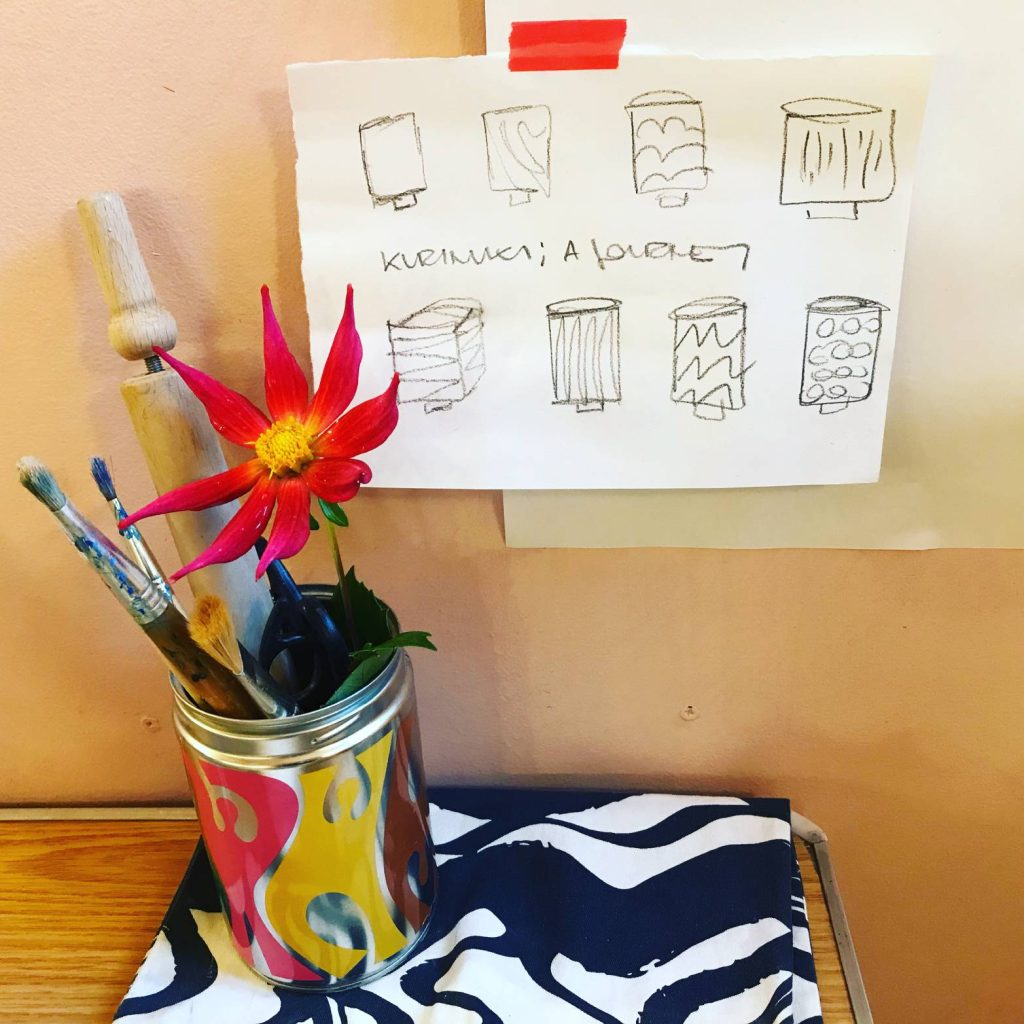

For months now I have been working and drawing, sketching, and also researching and studying pottery by contemporary potters and makers here in the UK and abroad. When I arrived at the Sanctuary I was ready to start my research on hand-building free form-making of vessels and sculptures using traditional hand-building techniques such as coiling and pinching. But the space took me back to one of my favourite pottery techniques called Kurinuki.

Kurinuki is a Japanese carving technique in which a piece is hollowed out from a solid block of clay. The exterior of each piece is created by faceting, stretching, and sculpting shapes at the surface with various tools and objects. The interior is then removed to hollow out and form a vessel. That hollowing out is a contemplative process that takes shape as you carve.

This very old Japanese technique perfectly combines the search for beauty outside the usual form and the wisdom that echoes true the centuries.

Kurinuki is also an instinctual and impetuous way of working with clay. Rather than symmetry and precision, the emphasis is put mainly on allowing the form to evolve impulsively allowing the lines of form to reveal themselves during the making process. The Kurinuki method of making is all about energy. The motion is quick, but it’s not just the speed. It contains momentum.

While I was carving out / hollowing the block of clay I was searching for a new (for me) explanation of the concept of void .. when by what we can call synchronicity I found some poems in a box for meditation just there waiting for me.

The Void is not wanted for its own sake –but it is firmly believed… that once the mind is emptied and the mental processes stopped, the deep power or light, which normally lies hidden and inactive within everyman, rises and shines forth by itself.

That empty sacred space was now filled with joy in the making and creativity and writing, reflecting, clay and sculpting tools, bags of clay, turntables, prototypes, sketches, drawing, sketchbooks, pieces of barks, leaves found outside dropped from the beautiful trees bathing in autumn colours.

And there was chaos too. But from that creative chaos… great things are emerging.

And as I read somewhere… “This experience will go well beyond the calendar week in which it is used”.

Indeed.

And since I left Hawkwood, I didn’t stop making… And at the time I am writing not all the planned work is finished and some of it hasn’t even begun. But I am still feeling anew, afresh, ready to keep going but with a different speed or no speed at all.

Full credit to Mari Balsama Wilson, with thanks to the DCMS & Arts Council England for their funding.